DAVID McDONALD - "Tiny Histories, 2005-2010"

March 13 - April 10, 2010

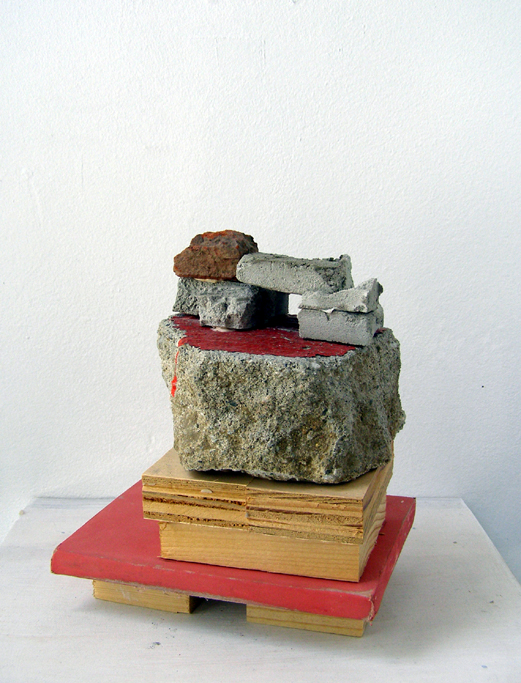

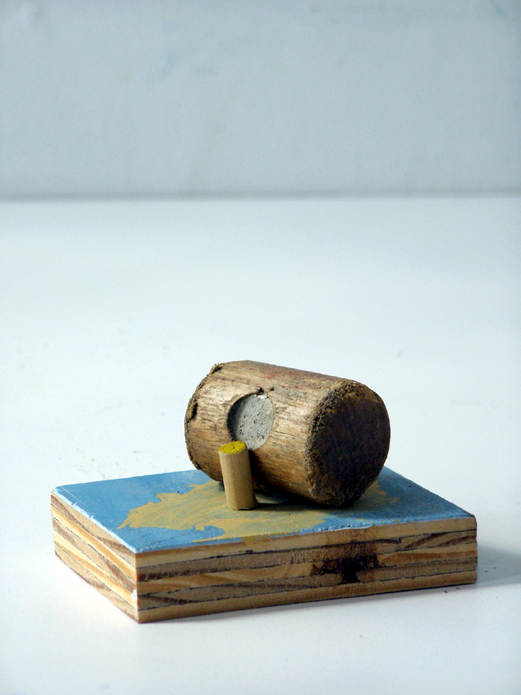

As a sculptor, David McDonald has routinely embraced the small and the modest. The quantities of materials he utilizes bricks, plaster, cement, wood, paper, cardboard seldom amount to more than what you might find in a scrap heap, in the bottom of a bucket, or left over on a mortarboard after you'd used the rest of the materials to make some big thing. His largest works are no bigger than a refrigerator, while most could be toted inside an igloo cooler. His pair of 2008 exhibitions at Jancar and Jail Gallery were respectively titled "Un" and "Minor Monuments," and following in this line, his current show at Jancar is titled "Tiny Histories, 2005-2010." Arranged chronologically along a shelf that wraps three walls of Jancar's backroom, the "histories" are indeed tiny even to the eyes of those familiar with the usual size range of McDonald's sculptures. But miniature doesn't equal minor; the best of these are stealthily compelling. That said, they're not for everyone. Kin to an odd lot, including works by the likes of Robert Rauschenberg, Donald Judd, Richard Tuttle and Lynda Benglis, they fuse the tradition of art of the ready-made or found object McDonald often makes bits and pieces that he then treats something like found objects with the traditions of assemblage, minimalism and postminimalist explorations of visceral materiality. The result is a kind of scrappy minimalism, rooted in the compounding of cubic and cylindrical forms, often caught in a tension between order and disarray, and washed over with pleasure taken in the organic and handmade. The crafting technologies that go into their manufacture rarely exceed the basics of stacking, gluing or nailing. In fact, it won't be hard for a lot of viewers to see them as bits of stuff stacked up something like three-dimensional doodling but it's a mistake to write off these amalgams of cast-offs as toss-offs. Far from it, they're devotional; their seeming casualness is the product of great care. That care and devotion can go astray, however, and despite McDonald's tendency toward the reductive, there are a couple of objects here that fall into a fussed- and doted-over preciousness, while a couple of others seem something like the sculptural equivalents of offspring only their parents could love. But the majority such as a work that consists of what looks like the head of a small mallet, minus its handle, sitting atop a little plinth of wood with a lone peg, or another in which the tips of pickets or wooden stakes affixed to a stubby column congeal into an encapsulated fusion of minimalist and Gothic architectural lines hit it just right, allowing viewers to share in McDonald's fascination with how nearly unnoticeable parts can add up to humble yet memorable and evocative sums. Such transformation is the primary story these works collectively tell, but parallel to this is one of imagination, both in the creative impulse of the artist and in the stories these sculptures begin to spark in the viewer's mind. - By Christopher Miles published: April 08, 2010

Tiny History 11

Tiny History 23

Tiny History 36

Tiny History 42

Installation View

Installation View